Hurghada: Red Sea Wrecks

The Red Sea, its reputation precedes itself. The beautiful red-orange desert mountains stand over the unexpected and contrasting blues of the water. The calm and clear waters hide much below. Under the water is a rainbow of colors, and among the fish and corals, are the remains of many ships.

Contributed by

Factfile

Brandi Mueller is a PADI IDC Staff Instructor and boat captain living in the Marshall Islands. When she’s not teaching scuba or driving boats, she’s most happy traveling and being underwater with a camera.

For more information, visit: www.brandiunderwater.com.

The Red Sea has been deceitful to many captains over time. The beautiful reefs that divers dream about here have also caused many a ship to meet its end. Sailors thought they were safe after clearing the challenging and narrow Suez Canal only to run aground or hit reef just outside the canal. Misjudgment and bad weather as well as numerous wars have laid the stage for the demise of many ships.

Although a popular dive location for Europeans, I (coming from the United States) knew very little about what I would find. I had always heard about its fantastic reputation and was excited to discover there were so many wrecks (which I happen to like very much).

Not only are there wrecks, but there are wrecks with really great stories behind them. Gold coins, wars, motorcycles and even toilets—who knew? I love nothing more than a good story and a good dive to create more diving stories to tell over a few drinks back on the boat. Lucky for me I had a week on Emperor Diver’s MV Superior liveaboard and a fantastic group of Finnish and Irish dive buddies.

The hardest part was that there were so many wrecks with so much to see on each one. I wanted to dive them over and over again. The dive guides correctly assured me that the next one would be just as good, if not better.

Diving out of Hurghada in March, the water temperature, frosty 22°C (70°F) was a bit colder than I expected (I hadn’t done my research before arriving). My first giveaway that the water would be chilly was when my boat mates were unpacking their drysuits!

Luckily, the diving was so good that I didn’t notice I was cold until the safety stop. With so much to look at and so many things to take photos of, I hardly had time to notice I couldn’t feel my toes.

Diving the wrecks

SS Thistlegorm. The World War II British Supply Ship, SS Thistlegorm, had left Glasgow, England, on 2 June 1941 loaded with military supplies headed for Alexandria, Egypt. Due to German and Italian forces in the Mediterranean, she made the long trip around via Cape Town, South Africa, refuelled and headed up through the Red Sea towards the Suez Canal.

Passage through the Suez was dependent on how many other ships there were, enemy activity, and in the case of the Thistlegorm, two ships had collided blocking the entrance of the canal, forcing her to wait before continuing. She was moored at Safe Anchorage F in September, awaiting the call to continue up the canal.

The Thistlegorm waited for two weeks and on October 6, in the middle of the night, two bombs were dropped on her, both hitting a hold with stored ammunition causing a huge explosion and sinking the ship. Two Heinkel He-111 aircrafts had been dispatched by the Germans from Crete to find and destroy a rumored ship carrying 1,200 British troops, and these aircraft were headed back after an unsuccessful hunt. They spotted the Thistlegorm at anchor in the moonlight and decided to release the unused bombs. The explosion almost tore the ship in two, and towards the stern, the ship seems to have peeled away leaving a distinct missing section of the ship.

While passing through Cape Town, the HMS Carlisle had joined the Thistlegorm and was anchored nearby also awaiting passage. The Carlisle rescued what crew it could, but nine of the 48 didn’t survive.

Launched in 1940, the Thistlegorm was built as a steam, single screw cargo ship. She only had four voyages, the fourth being her last. Her completed journeys were to North America to bring back steel rails and aircraft parts, Argentina for grain, and the West Indies for sugar and rum. To Alexandria she was carrying Bedford trucks, BSA 350 and Norton 16H motorbikes, boxes of rifles, aircraft parts, ammunition, tires, Wellington boots, torpedoes, tanks, two locomotives and other military supplies.

On our first dive, there was some current, which is common, and we used a surface line to pull ourselves up to the bow mooring and decent line. We descended forward of the ship’s bomb destruction towards the bow and entered the interior of the ship to visit holds #1 and #2. The first thing I noticed inside the ship was motorbikes upon motorbikes stacked in the beds of trucks. Three bikes to each truck and with many of the trucks you could see through the roof of the cab to the driver’s seat, clutch, pedals, and a few steering wheels.

Continuing over the trucks there were stacks of tires in any extra space in front of and behind the trucks. Schools of squirrelfish seem to have made their homes in the ‘tween decks of the ship, and they hovered above the trucks and motorbikes. A diver was waving his flashlight at me frantically summoning me over and pointed out a massive green moray eel coming out of a crack between a truck cab and bed. Upon closer inspection, the eel seemed to be guarding a Wellington boot.

The trucks and motorbikes seemed to never end, and in the back of one truck, our dive guide pointed out a battery which divers had rubbed clean of algae to show its brand. It is stamped with “Lucas, 1941, Birmingham England, Lead Acid”. Swimming through the holds, there is a lot of outside light and quite a few exits if one wants to get out of the ship.

On a second dive, we dove the outside of the wreck first visiting one of two LMS Stanier Class 8F steam locomotives, destined for Egyptian Railways, that had been carried on the deck of the ship. Both were hurled off the ship in the explosion, landing one on either side of the wreck. On our way back to the ship towards the stern, there was an upside down tank on which one could clearly make out the caterpillar tracks.

On the stern, the Thistlegorm was armed with a 120mm (4.7inch) anti-aircraft gun and a machine gun (the latter being attached after the construction of the ship). Both of these guns are still intact, the forward gun pointing toward the sea floor and the machine gun outward horizontally.

Aside from all the exciting artifacts and historical WWII relicts, the Thistlegorm is teeming with marine life. We saw several crocodile fish lounging on the deck, the holds were filled with colorful reef fish, batfish patrolled the decks, and pink and orange anthias guarded the soft coral-covered winch.

The Thistlegorm is one of the most popular and most dived sites in the world, and it’s easy to see why. The cargo it contains makes for an exciting treasure hunt with unsuspected war artifacts found around every corner. Its max depth is around 30m (100ft) making it easy for recreational divers and allowing for a fair amount of bottom time. Jacques Cousteau was the first to locate the wreck in 1956 using knowledge from local fisherman, but it was not found again and dove until the early 1990s.

Unfortunately, time and extensive use is taking its toll on the wreck. Rusting from more than 70 years in saltwater as well as many boats mooring directly to it in weak spots have caused collapses. Sadly, many artifacts have been removed from the ship as well; Cousteau, himself, took a motorcycle, the captain’s safe, and the ship’s bell. Divers have removed many of the small objects such as steering wheels and parts of the motorcycles over time.

Even with the wreck pillagers and dive boats and saltwater taking its toll, the Thistlegorm is a fantastic wreck dive. Multiple dives are needed to see the majority of it, and even after many dives it would be tough to get bored. Liveaboards frequent the dive site. Being close to Sharm el-Sheikh and Hurgada, day boats can easily get there.

Giannis D. Shab Abu Nuhas is a reef that is just below the surface near the Straits of Gobal, a very busy shipping lane. This hidden reef has been the demise of more than one ship. In fact, the wrecks of five ships can be dived off Shab Abu Nuhaus: the Giannis D, the Carnatic, the Chrisoula K, the Kimmon M, and the Marcus.

The Giannis D had left the Croatian port of Rijeka in April 1983, carrying wood to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and continuing on to Hodeidah, Yemen. Having made it through the Suez Canal, the captain thought they were in the clear and went to sleep, handing the vessel over to his officers and giving the orders of “full speed ahead”. Shortly after, the ship hit the reef and sank.

Having originally been launched as the Shoyo Maru in 1969, the 99m (325ft) long and 16m (52ft) wide cargo vessel was built in Japan. She was sold and renamed the Marcos in 1975, and sold again in 1980 to Dumarc Shipping and Trading Corporation and named the Giannis and D for Dumarc.

Sitting at a 45 degree angle on her port side between 6-27m (20-90ft) our dive guide took us through the interior of the stern. The slight tilt made it feel as if we were swimming through an underwater fun house. There isn’t too much in the way of artifacts inside the ship, but the engine room is easily accessed with machinery, gauges, handles and levers still intact.

The fish life is prolific with many species of reef fish calling the shipwreck home. A large mast extends horizontally from the ship and is covered with hard and soft corals. It appears to be its own little mini reef, and I saw emperor anglefish and parrofish there. Hanging down from the mast are he original rigging lines, also growing pink soft corals. The collapsed midsection harbors batfish and crocodilefish.

SS Carnatic. Another casualty of Shab Abu Nuhas reef, SS Carnatic was sailing to Bombay from Suez with 34 passengers and 176 crew, carrying cotton bales, copper sheeting, Royal Mail and GB£40,000 of gold coins. In the dark early hours of 16 September 1869, the ship hit Shab Abu Nuhas. Captain Jones assessed the damage and decided the ship was okay for the time being. He knew the P&O Liner Sumatra would be passing by soon. He decided to keep all passengers on board and continue business as usual until the Sumatra showed up to rescue them. Passengers were told not to worry and instead to prepare themselves for dinner.

Passengers asked the captain multiple times to take them to Shadwan Island some three miles away by lifeboat. All requests for transport were denied, as he kept hoping for the Sumatra to pass by. Becoming more persistent as time went on, the captain finally gave the okay for passengers to be put into the lifeboat.

It had been a day and a half since they ran aground. As the first four passengers were being put in the lifeboat (woman and children first) the Carnatic suddenly broke in half. The aft section of the boat sank quickly with five passengers and 26 crew. Soon, the rest of the ship fell onto its port side sending everyone into the water. With many heroic efforts, the remaining passengers were rescued and transported to Shadwan. Eventually, the Sumatra passed by and rescued those left.

Today, the wooden decks of the 90x12m (300x40ft) ship have rotted away leaving only the steel hull, with its iron supports and cross-members. The shallowest part of the ship is at 17m (55ft) and the deepest at 27m (88ft). It is lying on its port side.

The iron ribs were extensively draped with soft coral probably due to lots of water, nutrients and sunlight being able to pass through the beams. The bow area was packed full of glassfish, which hardly even tried to move out of the way when a diver swam through. Near the bow, dozens of small pipefish were free swimming just off the beams in search of breakfast.

The middle section has mostly collapsed but the stern is intact and the prop sits in the sand. A very photogenic davit encrusted with corals extends out from the stern section, and as I was framing a photo with the davit and the sun behind it, a group of four large spotted dolphins swam by our group of divers.

Because of the large quantity of gold and copper on the boat, Lloyds of London sent one of their best salvagers to the wreck. All the gold was reported found as well as much of the copper and mail, although there’s still a rumor that gold coins may be found around the ship. I had a quick look, but sadly, didn’t find any.

Rosalie Moller. Another loss of WWI, the Rosalie Moller was built in 1910 in Glasgow by Barclay Curle & Co under the name Francis. The 108m (355ft) ship was sold in 1931, renamed, and started sailing in China. When the war broke out, she was moved back to Liverpool and placed under the command of Captain James Byrne, transporting goods for the Royal Navy.

In July 1941, she was carrying Belgian coal, highly coveted during the war because it was supposed to burn longer and created less smoke, to Alexandria.

With the Mediterranean off limits because of German and Italian forces, she sailed the long way around via South Africa. Having gotten near the Suez Canal, just like the Thistlegorm, the Rosalie Moller took anchor to wait its turn to go up the channel. This ship's passage was also affected by the collision that made the Thistlegorm wait.

Anchoring in Safe Anchorage H, the Rosalie Moller had no idea about the loss of the Thistlegorm two days earlier, when during the night of October 8, two more twin engine Heinkels flew overhead and released two bombs, one hitting the Rosalie Moller, and she sank in less than an hour. Only two lives were lost, the rest of the crew were able to get to the lifeboats.

Sitting between 17 and 50m (55-165ft), this is one of the deeper wrecks we dived. With technical diving training and equipment, this ship is known for its penetrations particularly to the engine room, but we only explored the exterior, which is still very much intact and sitting upright. Visibility was a little murky, which is often normal, making the ship a little eerie and mysterious. We had no current, and that combined with the bottom composition probably led to the decreased visibility.

Descending from our boat, our first view was of one of two still upright masts wrapped with soft coral. Headed further down to the ship deck, we swam towards the bow. I looked into some of the deckhouse windows, and the interior was packed full of cardinalfish, glassfish and other juveniles. Near the bow, the deck gear was all still in place, and a crocodile fish was lounging in front of the winch.

This site is a popular place for a tiny, but very pretty purple flabellina nudibranch. We found three of them during our short dive on the Rosalie Moller. Running short on bottom time, I headed back to the forward mast to ascend and saw several large tunas hunting around the wreck.

Dunraven. Sometimes the story of the finding of a wreck can be just as exciting as the account of its sinking. In the case of the Dunraven, in the 1970s, Howard Rosenstein was looking for a shipwreck to dive. Local fishermen provided him with the “GPS coordinates” of a site described cryptically: "There is a place out in the Gulf in the direction of the setting sun, far from land and at least three cigarettes from Ras Mo-hammed. Here, there is a reef which comes out from the sea to break the surface at low tide. Go to the end of this reef coming from the south east.”

Pulling out some charts, Howard Rosenstein got quite lucky guessing the exact spot. The ship wasn’t identified as the Dunraven for another two years, when engraved porcelain had been found with the name.

Launched in 1873, the Dunraven was capable of being powered by sail or steam. In 1876, the ship was on its way to Newcastle from Bombay carrying spices, timber and cotton. In good weather, the ship sailed straight into the reef near Ras Mohammed in the dark. The crew tried for 14 hours to get the ship off the rocks, finally succeeding, but it still capsized, sinking quickly. The 25 crew were rescued by local fisherman.

Mostly upside down and lying on her port side, the propellers are the shallowest point at 17m (55ft), and the ship deck sits in the sand at 27m (88ft).

With several entrance points into the interior, the Dunraven made for a fun dive swimming inside most of the upside down hull. We started the dive outside the wreck near the propeller (one of the shallowest points) which still has three of the blades intact. Coming around the starboard side, we entered the ship near the sand, which almost felt like entering a large dome. Light made its way in through the lower sides near the sand, with the ship overhead. Squirrelfish and goatfish schooled inside the wreck, and after exiting, a large napoleon wrasse paid us a visit. The area around the wreck was very nice reef with hard corals, sea fans, and lots of reef fish.

SS Kingston. All that remains of the Kingston, which sank in 1881 after running aground on Shag Rock, are the metal beams and hull. Sitting upright with its shallowest point at 4m (13ft) the ship remains are so overgrown with corals it's hard to differentiate most of the wreck from the reef. Many fish have made the wreck their home including many anthias and several schools of glassfish. Some of the more notable remains include four tall posts near the bow area standing straight up. At the deepest point, 19m (62ft), the propeller sits encrusted with coral and fan corals are growing on the hull.

The Kingston was a 78m (255ft) by 10m 32ft) rigged iron hull screw steam ship sailing from London through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal to Aden, Yemen, with a crew of 25. Once getting through the treacherous canal, Master Thomas Richard Cousins went to bed to sleep. Near midnight, the ship hit Shag Rock. In an attempt to save the vessel, the crew dumped a large quantity of the coal cargo. The ship was still afloat when the captain asked the passing steamship F.W. Ward to help pull her off. They declined but offered passage for the crew, which the captain denied.

Later the Columbian came alongside and tried to help pull her off, but couldn’t. A full day had passed when the ship started taking on water and the captain decided to have the crew abandon ship. Seventeen crew were given passage on the passing Almora, but the rest of the crew stayed onboard for another day and then moved to Gobul Island, staying four days before being rescued.

Jolanda. Often incorrectly spelled Yolanda, the Jolanda was a 75m (245ft) Cypriot freighter sailing from Piraeus to Aqaba with a cargo of toilets, wash basins and bathtubs. She ran aground near Ras Mohamed during a bad storm on 1 April 1981. After four days, the ship rolled onto the port side sitting at the edge of a wall. Until 1985, she was completely in recreational dive depths, but then the ship fell over the edge leaving only the toilet and bathtub cargo behind on the reef between 10 and 30m (32-100ft).

Close to the popular dive site Shark Reef, the Jolanda cargo is an unexpected sight underwater. We started our dive at Shark Reef drifting along in a slight current. The hard corals cover the sloping wall, which extends off into the abyss. Coming up on the Jolanda cargo, I first saw one lone white porcelain toilet sitting upright, as if it were waiting to be used. Continuing on they littered the sea floor sometimes stacked on top of each other and scattered in all directions. A small bit of metal ship structure was left as well, with the beams decorated by soft coral, and fish taking up residence underneath, in the shadows.

The ship was relocated in 2005 between 145 and 200 meters deep, but for me, the cargo was just as interesting, even without the ship.

Afterthoughts

The history that lies beneath the Red Sea makes it a playground for any wreck diving enthusiast. With so many ships having sunk for different reasons over many years, it has become an underwater museum decorated with the gorgeous and colorful corals and fish of the Red Sea. Tales of destruction and loss, wars, bad weather and just bad luck are as numerous as the abundant marine life of the Red Sea. As my week came to an end, I was already planning my return trip to see it all again and maybe check out the Southern Red Sea wrecks. ■

REFERENCES:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ss_thistlegorm

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ss_carnatic

www.aquatours.com

www.touregypt.net

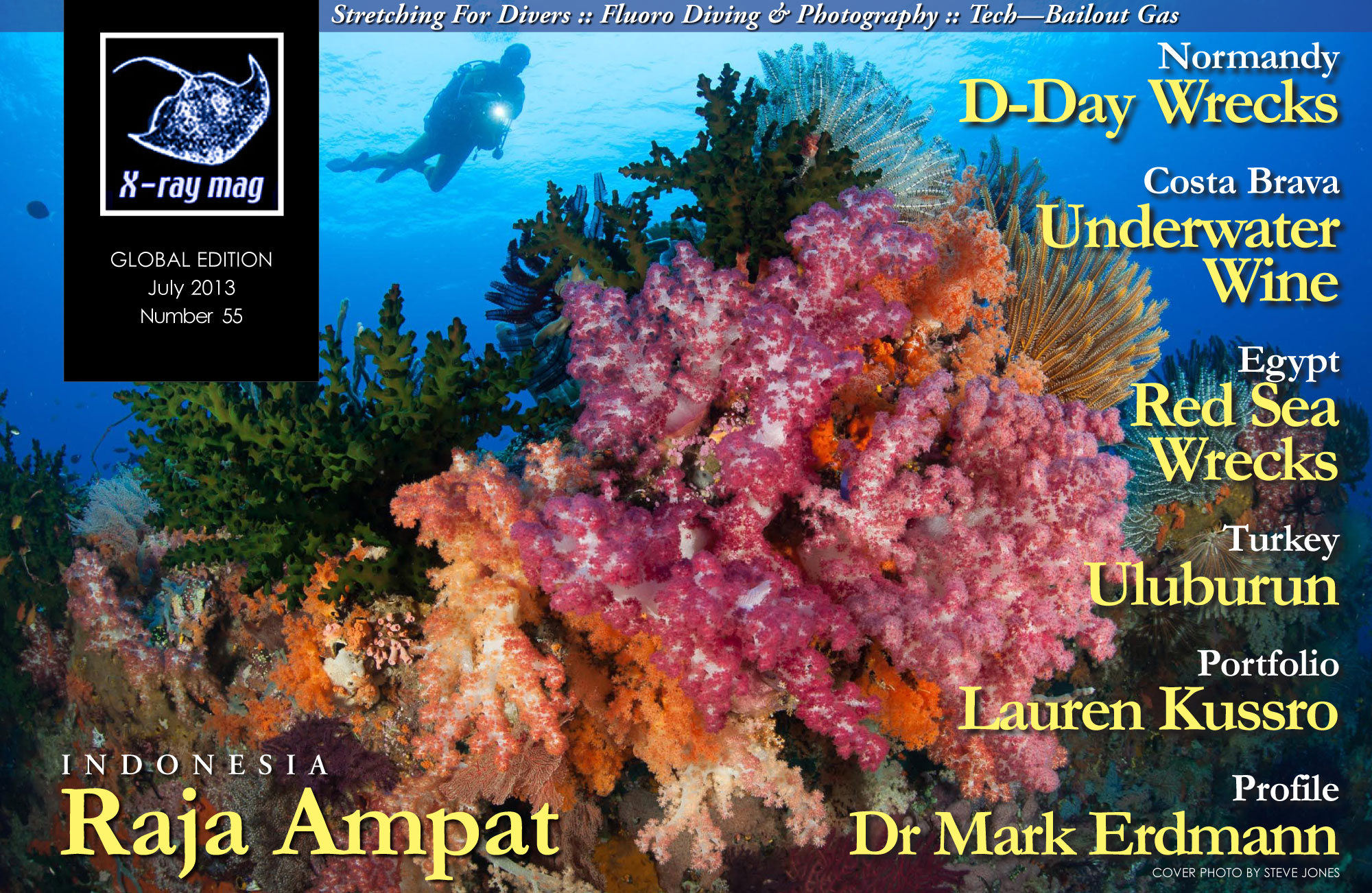

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #55

- Læs mere om X-Ray Mag #55

- Log ind for at skrive kommentarer