A powerful influencer of climate and ocean currents, the Atlantic Ocean is vast, stretching from the North Pole down to the South Pole. At around the middle of this massive system lie the Azores Islands, about seven hours flight from New York or approximately four hours from Lisbon. Silke Ptaszynski shares her adventure to the southernmost island of Santa Maria, with photos by Rainer Schimpf.

Contributed by

The island group comprises nine islands, each with very different characteristics. One thing they all have in common is their nickname: “The Green Islands.”

Winter rains are massive, and summers are mild, with temperatures seldom reaching above 27°C. Lush forests and desert-like areas are home to dairy cows and sheep. The locals are friendly, and safety is not an issue. Where else can you park at an airport for free, and leave the key in the ignition when you drop off your rental car?

The islands lie in-between the North American, Eurasian and African tectonic plates and are, of course, volcanic. Some of the islands still have enough volcanic activity to heat up the ground and create beautiful colourful lakes.

Santa Maria

The southernmost island in the Azores is Santa Maria. Here, the dominance of the Gulf Stream assures 16 to 20°C water temperatures most of the year; however, in summer, from August to September, water temperatures may rise to 27°C.

Santa Maria Island is where our adventure starts. The island is small; it takes only about two hours to drive around it and experience the highest point—close to 600m—at Pico Alto, with its dense forests of mammoth trees and tree ferns. The grassy areas at the foot of the mountain, where cows and sheep roam, are lush and green. Only two beaches can be found on Santa Maria Island: Praia de São Lourenço and Praia Formosa. Much of the rest of the coast is made up of sheer cliffs.

The topography underwater is similar, with a smooth sea bottom close to shore, and some hundred metres or so off the island, there is a deep drop into the Atlantic Ocean.

Deep trenches filled with tiny marine life such as plankton create amazing feeding opportunities for larger marine life, as the plankton move up towards the surface from underwater seamounts. The most renowned dive site is Ambrósio, which is only about seven nautical miles from the port.

The port of Vila do Porto is where it all begins. The marina is small and has a great restaurant called Clube Naval de Santa Maria, which offers snacks and drinks during the day, and superb dinners on most nights. Most dive centres on Santa Maria Island are based here as well, and head out to dive sites from the port on semi-rigid rubber ducks with 300HP motors.

Diving

Divers assemble in the morning at the harbour area. All the dive centres have dressing areas, and there are public toilets and showers. Dive courses are available and recreational diving can be done at a variety of national parks and protected areas.

Even though most reefs are rocky and barren, one will find a plethora of fish, moray eels, barracuda and groupers. The reefs are full of life and sometimes have spectacular topography too. There are even some cave-like overhangs, where cleaner shrimp can be found.

In general, recreational dives are double tank (nitrox is available), and it takes about 45 minutes to reach the dive sites, with intervals taking place on the dive boat. After the second dive, one can be back in port as early as 2:00 p.m. This gives you time to explore the island by car or scooter and enjoy the local sights and attractions.

Dive sites

Dive sites to visit if you are a certified diver or freediver are plentiful, but Ambrósio should definitely be on your must-do list. Ambrósio is like a superhighway and fast-food joint for all pelagic fish and sea life in the area, and is the best place to experience the abundance of marine life at Santa Maria Island.

Mobulas or sicklefin devil rays (Mobula tarapacana) can be seen in huge groups of up to hundreds of individuals during the season between June and October. In sequence, they spiral around the Ambrósio seamount, moving up to the surface where a buoy is anchored. Many divers and snorkellers enjoy watching this spectacle. Not shy at all, the mobulas come so close that one can easily experience these creatures up close.

Pelagic fish like barracuda, wahoo and dolphin are seen most often. The best part is that this area is also the hunting grounds for big tunas. Where else can one see both bigeye tuna and yellowtail tuna on the same dive?

Along with the entire archipelago of the Azores, Ambrósio has been declared a Hope Spot by Mission Blue (ed. – the ocean conservation nonprofit organisation and alliance led by oceanographer Sylvia Earle), being a critical site for ocean biodiversity. However, more local governmental support is needed to make this a reality.

This place is very special. Fishing is prohibited here, but fishing boats are nearby, fishing for baitfish such as snipefish, which fishers use to attract bonitos and tunas during the season. Sometimes, the fishing boats are so close that divers can see them while underwater. In the split shot, you can see the boats using water hoses, spraying saltwater onto the surface to create the illusion of panicked fish in order to attract bonitos. Funnily enough, snipefish will form a small bait ball under the keel of a fishing vessel to hide from the tunas.

Tuna

To see and experience fully grown tunas, one will need to travel a lot around this planet to find them. On our trip, during the season from August to September, we had plenty of occasions in which we saw bait balls of snipefish and loads of tuna in a feeding frenzy. More about that later...

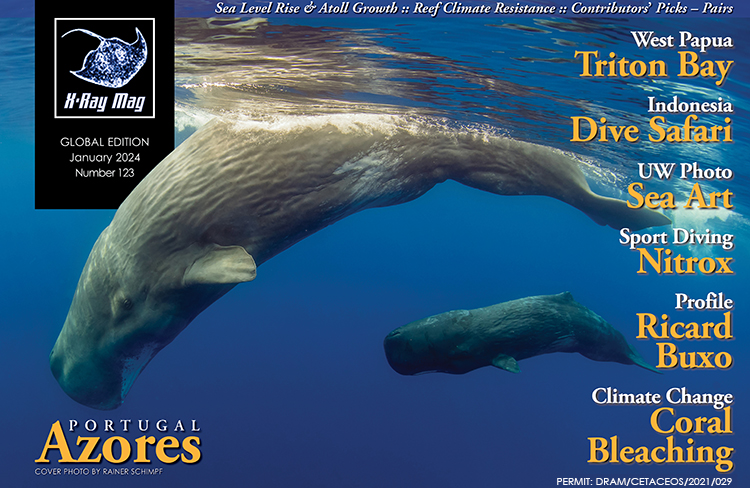

Due to the deep trenches and topography, sea birds and marine mammals such as common dolphins, bottlenose dolphins and spotted Atlantic dolphins often followed our vessel or were engaged in bait ball action. On our trips to Formigas Island, approximately 40 nautical miles north of the harbour, we encountered sperm whales and pilot whales; some skippers even had the privilege of seeing orcas.

In the Azores, it is prohibited to enter the water when whales are around. However, in the past, we were lucky to have had a special permit on hand, which gave us legal permission to photograph these majestic animals.

Formigas Islets

On our trip, we also had a chance to visit the Formigas Islets, which were rated by Jacques-Yves Cousteau as one of the best dive sites in the Atlantic. Sometimes referred to as the Formigas Bank, the islets are a group of uninhabited rocky outcroppings in the eastern group of the Azores archipelago. They are 43km northeast of Santa Maria Island and cover a surface area of about 9,000 sq m. The submerged Dollabarat Reef is located in the same area. The only structure on the islets is a lone lighthouse, located on the largest islet, Formigão (Big Ant).1

The nearly 2.5-hour boat trip to the Formigas Islets was certainly worthwhile, because many of the previously mentioned marine mammals could be seen here, if one was lucky. The site offered a special dive with groupers, which were seemingly tame and generally enjoyed being photographed. There were also black corals in astounding formations on spectacular walls at deeper depths. Fish were plentiful as well; there were groupers, barracuda, jack fish and triggerfish, along with the odd mobula flying past. The chance to see hammerhead sharks was real as well. Absolutely worth a trip.

Returning to land, be sure to explore Santa Maria Island. The villages here seemed like they were from another time, and some ruins even showed evidence of earthquakes, which take place occasionally in the region. There were lots of great restaurants with offerings ranging from the local cuisine to Italian and German. Most restaurants were conveniently situated along the main road.

Expedition

The expedition was planned and executed in a different way. It was not an ordinary, “walk-in” dive trip, but a pre-planned and organised one. It was organised based on the operator’s previous experiences conducting sardine run trips in South Africa, except that it had been customised and implemented in a manner suitable for Santa Maria Island and the specific dive boat. Such an expedition is the specialty of Expert-Tours, which has been conducting sardine run dive trips for over 20 years.

The diving was part of this trip but almost secondary to the main objective, which was to experience the Atlantic Ocean and all it had to offer. As this did not come naturally, we had to search the seas and sail around quite a bit to capture underwater images of the unique aggregations of marine life that could be found here.

After launching the dive boat and assessing sea conditions, weather forecasts and the daily changing currents, we then focused on surface activity. Various bird species like shearwaters and seagulls would fly around a site, indicating the presence of prey, which meant fish could be found below.

At this time of year, there were mainly mackerel and snipefish. These fish were preyed upon by tunas, bonitos and blue sharks. So, to protect themselves, these small fishes formed bait balls.

Bait balls were what we were really after, with the best coming with schools of tuna in tow. Since the tuna were getting into a feeding frenzy, the surface of the Atlantic appeared to be boiling, with splashes and sprays visible from afar. To locate these bait balls, the birds were important.

Whale sharks

The second goal on the trip was to find the biggest fish in the waters of Santa Maria—the whale shark. These apex predators feed predominantly on plankton, but small fishes like the snipefish are also high on their list. Since whale sharks are not present all year around, the expedition takes place in August to September to increase the chances of encountering these awesome gentle creatures. Different sizes of whale sharks, ranging from 4 to 12m, were spotted and documented in the 2023 season.

Ongoing research is being conducted by Jorge Miguel Rodrigues Fontes, who has been tagging and marking whale sharks in the Azores to find out more about their distribution, movements and feeding habits. At present, little is known about where these giants travel to during the offseason and where they come from during the season. Hopefully, the findings of this research will help to further protect the whale sharks and their habitats in the open ocean of the Atlantic.

Back to the expedition, the holy grail would be to find a bait ball situation, with lots of sea birds at the surface, feeding tunas below the surface, and a whale shark coming onto the scene to feed. The whale shark cannot initiate the formation of a bait ball, so it follows the fast-moving tunas, which would drive the small fish up against the surface of the ocean. There, the small fish lose a dimension and are trapped against the surface, thus forming a bait ball.

This situation happens naturally and cannot be evoked. No one knows where or when it will happen. Therefore, the expedition is different from a normal dive tour or scuba trip.

The dive boat actively navigates the seas for hours on end, reading signs, with dive staff getting in and out of the Atlantic waters to check for bait balls, trying not to get too close to a potential bait ball or scaring away the sea birds and tuna, and potentially frightening the whale shark away. An experienced crew is essential for this.

It takes the entire team, finding the confidence and rhythm, to understand the best way to quietly enter and exit the water, and lots of sandwiches and energy bars to enable crew members to conduct this calorie-burning exercise for days.

With hard work, it eventually all came together for us, and we were finally in the water, slowly freediving and snorkelling close to a big bait ball of snipefish. The bigeye tunas were super-fast and enormous, with some weighing more than 500kg. Being fish, they were not aware of what we human beings were and how fragile we could be in the water. So, one needed to have the big tunas always in sight, since you certainly did not want to be rammed by a tuna, inside the bait ball.

Rule Number One: Do not get into, or on top of, a bait ball!

We approached slowly. The sight of the tunas striking the bait ball at high speed was amazing to watch. The snipefish stood no chance.

Rule Number Two: Always scan for whale sharks.

Out of nowhere, the biggest fish on the planet, the whale shark, appeared out of the blue Atlantic, with an unshakable objective—the bait ball! Like a movie star making an entrance, the whale shark carved through the water, as if in slow motion, moving towards the bait ball, opening its jaws and sucking in the snipefish.

Its ability to swallow fish and water and filtering everything though its gills decreased the size of the bait ball instantly. Close-up photographs show that some of the snipefish were still alive and swimming inside the whale shark’s mouth for a while, until they were finally sucked into its stomach.

The waters around the bait ball were now full of particles, such as snipefish scales and excrement from the tuna, hampering the visibility in the waters of the Atlantic. In general, visibility in the Atlantic Ocean around the Santa Maria Island is more than 30 to 60m.

An extraordinary experience

So, what is so special about this site? Well, there are countless places on this planet where one may encounter a whale shark, but there are only a handful of places where you can see them feed, and very few spots where natural feeding can be observed. In other words, it is extremely rare to see and document it, and it is difficult to find. Skippers, operators and crew need to know exactly what to look for, and divers and freedivers need to be briefed properly to really enjoy and watch this amazing sight.

Depending on the phase of the moon and the currents, activities of this kind can stretch from the area of Ambrósio and along the entirety of Santa Maria Island. Our four-week search for bait balls produced some amazing footage and left us with a deep respect for the coordinated hunting skills of the birds, tuna and whale sharks. As scientists continue to study this phenomenon, they will surely be able to glean much more knowledge from their data, so we all can learn more about it.

On days where a bait ball search was not in the plans, we dived several times at Ambrósio. Local government and tour operators maintain protections in the area, so only specific slots for a limited number of boats were available.

Mobula rays

Another secret is where the mobula rays travel to or from. According to reports, some tagged individuals have been seen in winter in the Kap Verde Islands, a distance of almost 2,500km away. It seems they travel along the deep underwater trenches, following the best food sources of plankton and ideal temperatures. On our trip, mobula rays were spotted, some heavily pregnant, and we were able to document one that had a very “full” belly at Ambrósio.

Ambrósio is a protected dive site, approximately seven miles from the port of Santa Maria Island. The underwater sea mount of Ambrósio is about 45m deep at its shallowest point. A set of buoys is permanently anchored there, where dive boats can tie up. Dive time was limited to a maximum of 60 minutes, but this gave one enough time to be enchanted by the fairy-like movements, acrobatics and synchronised swimming of the mobula rays.

At Ambrósio, they followed the upward current from the deep, at almost the exact same spot every 15 to 20 minutes. As they emerged from the deep, gliding up nearly to the water’s surface, one first saw their white undersides in the distance. Like dancing ballerinas, they came closer and closer to us divers, who were either diving freely around the anchor line of the buoy or holding lightly onto it, depending on the current.

Getting as close as one metre away, the mobula rays approached us in a cursory manner. We each got to shoot several images, and some amazing moments were captured! Several pregnant mobula rays were documented.

The hope in the scientific community is that Ambrósio may be a breeding ground or nursery for these majestic animals. Scientists like Alice Soccodato are doing their best to protect and study the species in the area.

Sperm whales

In the blue Atlantic, one may encounter sperm whales as well. However, it is prohibited to snorkel, swim or dive with these animals. We were privileged to have a special permit and thus had some in-water encounters with the sperm whales. Permits are only available for photo and film crews and can be applied for at the appropriate governmental institution.

Good to know

So, what does it take to have a successful expedition to Santa Maria Island? Choose the right tour operator. We did not just come for a dive trip, but for a sardine run adventure in the Atlantic. A minimum number of divers/freedivers on the dive boat is required. However, with more than six people, it becomes too crowded around the bait balls. This is also true at the Ambrósio site, as there would be too many bubbles from dive tanks in your underwater photographs.

A full charter option is best. An experienced crew and a proper briefing will help to find the best way forward and guarantee success in taking underwater images. The best time to travel for what we experienced is definitely August to September; however, all the dive centres on Santa Maria Island are open from May to October each year.

Currently, there are three permanent dive centres on Santa Maria Island: Wahoo Diving, Haliotis Dive Centre and Manta Maria Dive Centre. Nitrox is available at all the dive centres.

Only one dive operator conducts full charter sardine run adventures in the Atlantic, and that is Expert-Tours. For a really great adventure experience, go to: expert-tours.de. Preplanning and booking is essential, so plan at least one year ahead!

Get a rental car in advance and book your accommodation. Some recommended hotels include Hotel Colombo, Charming Blue, Praia dos Lobos and Pousada de Juventude. There are decompression chambers on some islands in the Azores, but NOT on Santa Maria Island. So, make sure you dive safely and within your decompression limits. There are no dangerous animals or insects on the islands, and no extra vaccinations are required to travel here. It is a safe destination with zero crime. Flights from Europe and the United States are available almost daily with layovers at São Miguel and a connecting flight to Santa Maria Island. ■

1 HTTPS://EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FORMIGAS