A joint group of GUE divers from Norway, Sweden and Finland, led by project leader Gunnar Midtgaard, documented the wreck of the Blücher in Norway, and its condition, during the summers of 2011 and 2012. Mattias Vendlegård, who served on the photo team during the project, has the story.

Contributed by

Factfile

DIVERS OF THE PROJECTt:

PROJECT MANAGER

Gunnar Midtgaard

SUPPORT MANAGER

Ronald Larsen

VIDEO TEAM

Gunnar Midtgaard, Norway

Fredrik Taule, Norway

Martin B. Karlsson, Norway

Bjørn Opperud, Norway

Martin Nålsund, Norway

Hallvard Opheim, Norway

Jørgen Birkhaug, Norway

Anders Bertelsen, Norway

SUPPORT DIVERS

Dan Morten Tryli, Norway

Daniel Kressin, Sweden

Erling Hoydal, Norway

Kacper Rybakiewicz, Norway

Aleksander Thomassen, Norway

Edward Smith, Norway

Garm Sätre, Norway

PHOTO TEAM

Mattias Vendlegård, Sweden

Bjørn Stubne, Norway

Daniel Kressin, Sweden

Erik Hultén, Finland

Fredrik Gestranius, Finland

Mattias Sjöström, Finland

We slowly descended through the cold dark water. With every metre, the darkness became more and more dense, and the water slowly got colder and colder. Torchlight beams from our team were all pointing down into the darkness, all of us searching for the same thing—the thing we knew was down there, the thing that had brought us all together, and the reason why we were here.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, Blücher appeared. Just a few metres in front of us, we saw her as a reflection of dark steel. Blücher was trying to hide her size in the darkness, but we all knew that we were tiny compared to her—just tiny visitors at her final resting place.

When you land on the wreck like Blücher, a feeling always comes over you. This machine of war was sunk in battle, and when it landed on the bottom of the Oslofjord, Blücher did it while fighting, and that is the way she was frozen in time.

History never feels as alive as when one dives a wreck that had fought for its very survival. One can see the traces of the battle: empty shells, guns searching for a target, misshaped metal, and boots of sailors who never made it back to the harbour from which they set sail.

This is history in its most real and naked form. There are no signs or posters, tour guides, restoration plans or souvenir shops on wrecks. Wrecks are a frozen moment in time, a moment of panic and dismay. When the rest of the world moved on, time on Blücher stood still. Here it is still the 9th of April 1940. But nothing lasts forever, and slowly, this magnificent piece of history is disappearing.

Eventually, the harsh environment, which surrounds Blücher, will defeat her. Blücher was not made to be here; yet again, she was fighting a losing battle. One day, nothing will remain of Blücher. That was why we were here, and that was why what our team did at this site was important.

April 1940

It was the night of 8 April 1940. World War II had started only seven months earlier in Poland, and Norway was just about to realise that it was next on the list for Hitler’s forces. As part of Operation Weserübung (code name for Germany’s assault on Denmark and Norway), Germany’s newest and most modern heavy cruiser, Blücher, was ordered to enter the Oslofjord together with the “pocket battleship” or Deutschland-class cruiser Lützow, the light cruiser Emden, three torpedo boats and eight minesweepers carrying a total of 2,000 troops.

The plan was to invade the Norwegian capital, Oslo, in a surprise attack. This was Blücher’s first mission, and the commander on board, Oscar Kummetz, believed that the heavily disarmed Norwegians forces would not have the guts or power to stand up against his modern heavy cruiser and the ships that followed her.

In the fjord, the Norwegians had Oscarsborg Fortress, but its commandant, Birger Eriksen, did not have much at his disposal to defend the capital. The fortress had only three 28cm Krupp canons dating back from 1892, and north of the fortress, he had the Kaholmen torpedo battery, which was equipped with only a few 45cm Whitehead torpedoes made in 1906.

The fort was understaffed, and the few men they had were neither trained nor experienced in combat. They were a mix of conscript recruits, chefs and medics, and none of them had ever seen or heard a Krupp canon in action before, and definitely had never fired one themselves. Commandant Eriksen’s lack of manpower meant that he could not even run all three of his cannons and had to settle with just two.

“Incoming warship with lights off at Filtvedt!” This report reached Eriksen early in the morning, and he knew that the enemy now was just six nautical miles from his fortress. Eriksen knew that the fortress was more like a museum than a modern fort, but the sense of duty and loyalty to his country made him shout out the order: “Fire with full power!”

With Eriksen himself working on one of the canons, they fired as soon as they had Blücher in range. The first round fired hit Blücher. One of the shells hit an ammunition storage, causing a massive explosion that set the heavy cruiser on fire. Despite this hit, a ferocious battle broke out between the fortress and the advancing Blücher.

But Blücher did not know about the torpedo battery at Kaholmen, and as soon as she came in range, they fired. Despite their age, the torpedoes did their job and hit her hard. At this point, Blücher’s rudder had stopped working, and she had begun to keel. About 1,000m after she passed Oscarsborg Fortress, Blücher went down into the fjord forever.

The faces and screams of wounded sailors swimming for their lives in the mix of cold water and burning oil were terrible. The pocket battleship Lützow and light cruiser Emden now had the full attention of the Norwegians and started getting bombarded. The emergency command of full speed astern was given, and the ship reversed away from the shelling, as they believed that Blücher had hit mines.

The sinking of Blücher caused a delay of the German attack on Oslo. Thanks to this delay, the king of Norway and members of the Norwegian government were able to escape, and so the Norwegian government therefore never surrendered to Nazi Germany.

Present day

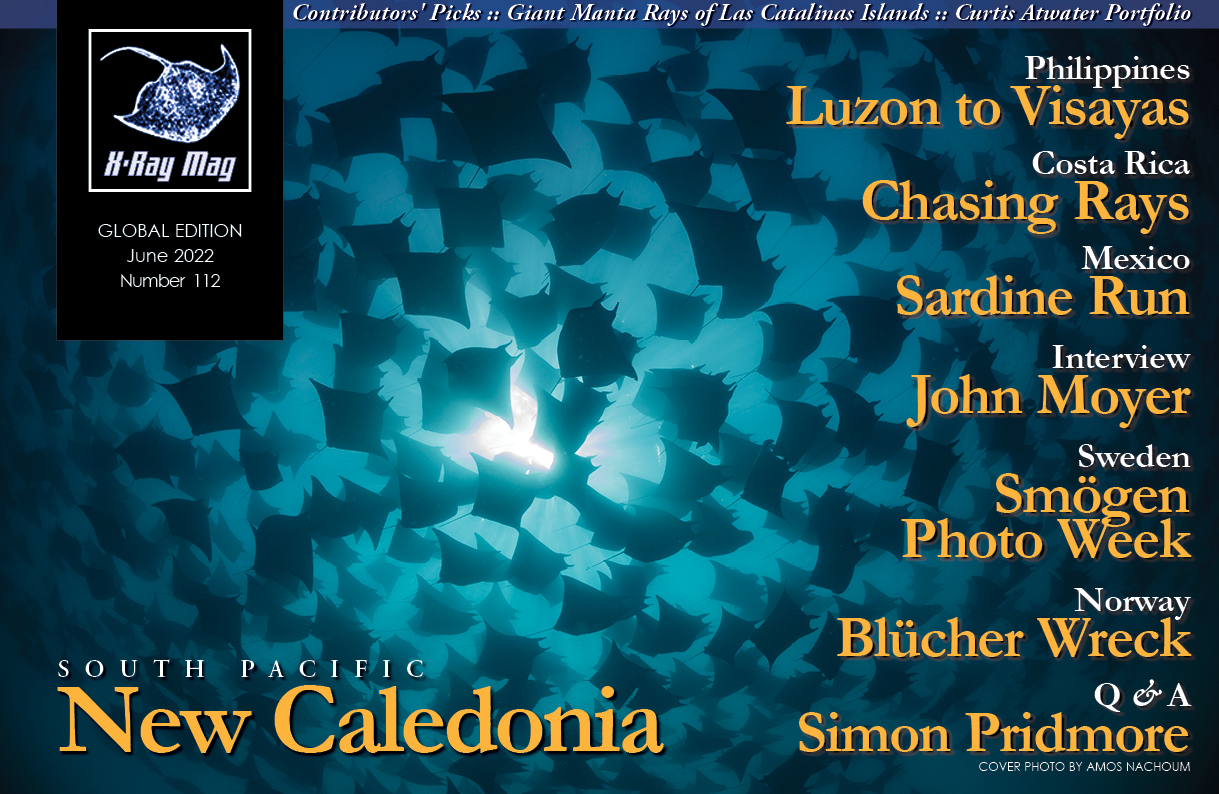

Today, the massive wreck of Blücher rests on the bottom of the Oslofjord at 90m deep. During the summers of 2011 and 2012, a joint group of GUE divers from Norway, Sweden and Finland, under project leader Gunnar Midtgaard, documented the wreck and its condition.

The wreck is almost completely upside down and rests on the port side and the bridge. Her mighty 2x20cm front canons are hidden in the sea bottom, and today, only the back corners of the canons can be seen. The two 2x20cm canons from the stern have fallen off the upside-down deck and now lie also upside-down on the seafloor.

All twelve of the 10.5cm canons, as well as all the anti-aircraft guns, are still in their original place on the ship. It is easy to get the feeling that there are canons and guns everywhere one looks when one dives this mighty war machine.

Blücher torpedo batteries are still in place with some of the torpedoes that never got the chance to spread their destructive power. Here, you can also see that the teak deck is still in good condition despite spending more than 70 years in the waters of the fjord.

The project

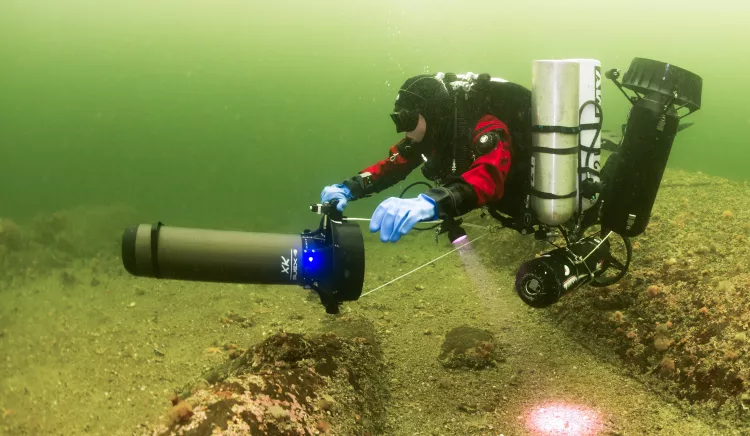

The goal of the project has been to document Blücher and its current condition. As mentioned earlier, the project has been run as a joint project with GUE divers from Norway, Finland and Sweden. The diving within the project was conducted in the summers of 2011 and 2012, with deep dive teams that took video footage and photos of the wreck. The deep dives were conducted with teams of three to four divers, including two HMI lighting divers, one underwater photographer/videographer and a dive model.

All the deep dive teams were supported by a dedicated team of support divers in the water, assisting the deep dive teams with gas, nutrition and equipment. Fjords Underwater Explorers (FUE) from Norway hosted the project and managed the logistics, with boats and gas fills. The gas fills were a critical part of the project, and all dives were done with 12/65 and open circuit. This gave the deep dive teams a 25-minute bottom time, with a total runtime of 2.5 hours. Each deep dive team did three dives, spread out over three days.

Even though all the dives were done during summertime, water temperatures at the bottom never rose over 5°C, or 15°C in the shallower depths of the decompression stops. Diving to these depths, for so long, in such cold waters, demanded a lot from the divers, their equipment and routines. All of the divers involved in this project were experienced in both cold-water diving and deep diving, a crucial requirement in order to keep the diving safe, while at the same time, producing the results that the project was aiming for.

There was no daylight present at the 90m depths in the Oslofjord, and Blücher lay in complete darkness. Even with two HMI lights per team, the visibility was never more than 5 to 10m, something which demanded great team awareness and navigation skills from all the diver who tried to dive the wreck.

It is important to remember that Blücher, and the context in which she was sunk, is an important piece of history, as well as a gravesite for several hundred sailors. Anyone who dives this wreck should keep this in mind and always dive with respect.

To everybody interested in this project or the history of Blücher, we are very proud to announce that a documentary video was launched in 2013. The release date is not yet set but keep your eyes peeled, as it is well worth watching for anybody interested in diving and maritime history.

Special thanks go to Fjords Underwater Explorers (FUE) who managed all the logistics of the project.