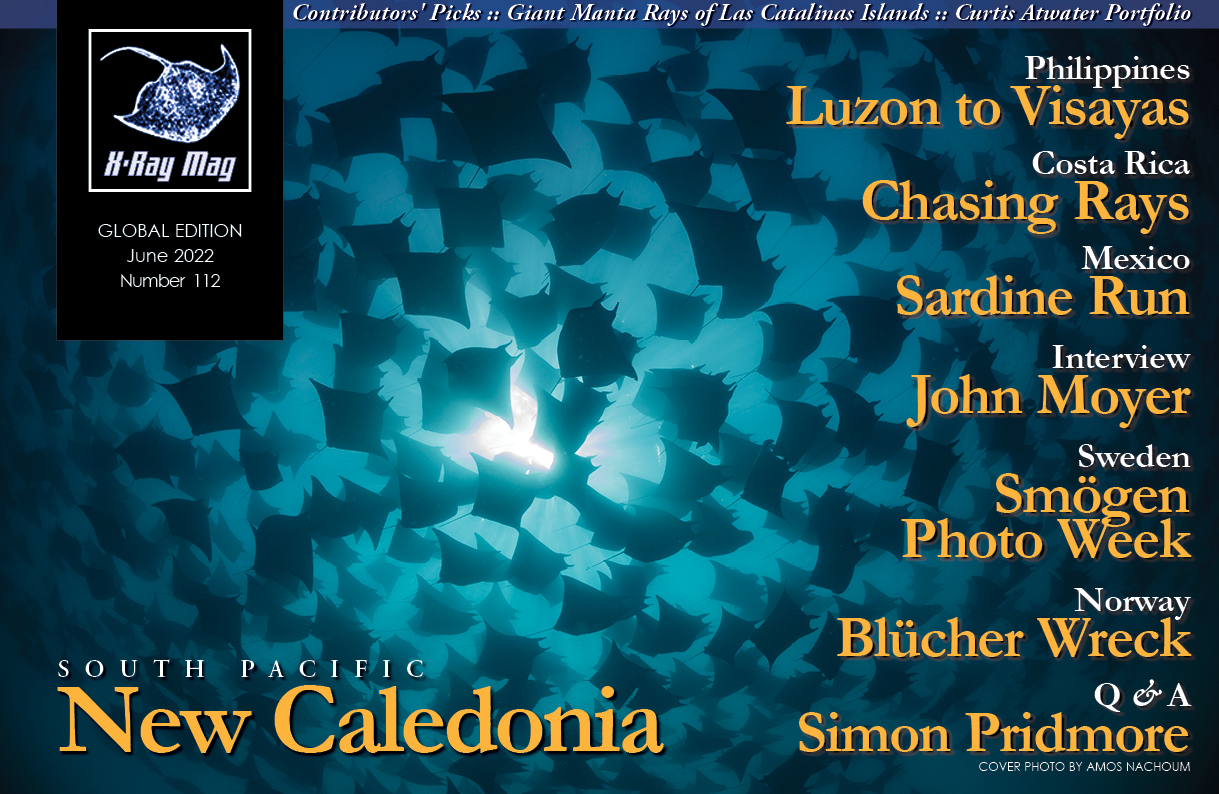

Although striped marlins (Kajikia audax) are slower than some of their billfish cousins, their 50-mph speed was plenty fast for me. I tried to swim alongside this stealth bomber of the sea as it worked a baitball to separate individual sardines from the silvery mass. Amos Nachoum has the story.

Contributed by

Factfile

HOW TO DIVE IT

GETTING THERE: From Europe via Mexico City, there are flights directly to La Paz, and my team will pick up arriving guests at the airport. From the United States, flights are available to San Jose del Cabo, and my team will pick up arriving guests from there too. Check with your tour or travel agent for the best flights.

SEASON: The prime time for the Mexican Sardine Run is November through December. We avoid the weeks when there is a sport fishing tournament, due to unfair and risky competition in the water.

ACCOMMODATIONS: BigAnimals expeditions offer the one and only liveaboard dive operation with exclusive service for three guests.

DIVE OPERATORS: We accommodate our guests onboard the 45 Catamaran Mango Wind, with the support of a local fisher and its own panga. The advantage of the liveaboard operation is that we save four hours daily crossing through Magdalena Bay to reach the action zone. We reach the action early every day and stay with the action after everyone leaves, to catch a glimpse of the sunset light.

GEAR: Bring at least a mask, fins and a snorkel. Freediving fins are not a must but will be more efficient for those with a powerful kick. A wind- and waterproof jacket, a warm fleece, sunscreen and sunglasses are good to have.

PHOTOGRAPHY: All kinds of cameras will give you amazing images. Telephoto lenses are good for topside photos. There is such a wealth of photo opportunities you will want something to capture the scene. For underwater photography, plan for wide-angle to super-wide lenses. You will not need strobes.

Sponsored by BigAnimals.com

While getting outpaced by sailfish and black marlin might be important to striped marlins trying to elude predation, they are so much faster than freediving humans that we do not usually get close to one. But the Mexico sardine run was not normal circumstances, and the marlins were not swimming away. They were swimming around, over, under and through a baitball. If you can stay with the baitball, you can stay with the marlins.

For this reason, underwater photographic encounters with marlins are now very popular in Mexico. It also helps that travel to Mexico is relatively easy, and the seasonal reliability of the sardine aggregations and the attendant predators provides a high probability of a successful encounter. It is the wild ocean and not an aquarium, so there are no guarantees, but divers and dive operators have refined the protocols for finding baitballs. Sailfish appear off the coast of Isla Mujeres and Cancun from January through March, and striped marlins are accessible at Magdalena Bay (Bahía Magdalena) on the western coast of Baja California Sur from November through January.

Small pelagic fishes (sardines, anchovies and mackerels) travel within the California Current, and the timing and location of their congregations influence the upper trophic levels in the food web. The North Pacific Current splits near British Columbia—the Alaska Current runs north to Alaska, while the California Current travels southward along the West Coast to Baja California. The small pelagics in the California Current are sensitive to environmental changes such as El Niño, making them susceptible to any resulting water variations.

Researchers have identified three prime locations along the southern part of Baja where the sardines spawn, lay eggs, hatch and mature: Magdalena Bay, Golden Gate Bank near Cabo San Lucas, and Finger Bank, a seamount near Todos Santos. Protected from the Pacific Ocean by the uninhabited sandy barrier islands of Isla Magdalena and Isla Santa Margarita, Magdalena Bay spans 31 miles along the western coast of the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. By autumn, the sardines have matured enough to attract large predators such as bonitos, striped marlins, Pacific sailfish, sea lions and even Bryde’s whales.

Hunting for a baitball

Finding a submerged ball of sardines in the open ocean is extremely unlikely by happenstance. Successful encounters occur when divers adopt the same protocols as the seasoned skippers of the sportfishing fleets, who travel 15 to 20 miles out to sea and typically 40 to 50 miles south of San Carlos. The frigatebirds follow the sardines, and we follow the frigatebirds. They are our eyes in the sky.

Frigatebirds search for a meal by flying high enough to see through the water’s surface to the frenzied activity below. As the birds find the baitball, their flight posture changes, and they circle while skimming low over the water.

We approached and saw the disturbance on the water’s surface as the swarming sardines jumped out of the water, creating shiny waves of spray and a cacophony of swishes and splashes as thousands of sardines seeked to escape the striped marlins below, only to be scooped up by the frigatebirds above. The sardines’ bad luck was our good fortune as we embarked on an extraordinary dive adventure.

Diving

“Go, go, go!” the divemaster screamed at us. I jumped into the warm water and searched left, right and below. The visibility was at least 80ft, but I did not see anything until a dozen or more striped marlins suddenly appeared out of the blue. I continued swimming and kicked harder in the direction the marlins were going. Tracking the marlins was tiring, but I kept swimming, confident they knew where they were going even if I did not. Then, at the edge of my visibility, I saw something big, round and dynamic.

As I closed the distance, the sphere coalesced into a frenzied, swirling mass of small silvery fish. The marlins were already on the attack. One after another, the marlins raced toward the prey, raising their sails, with their bodies streaming silver and blue, and reflecting dabs of yellow from the fading afternoon glow. Shaking their tails, they sped toward the baitball and then executed an impossibly tight turn to close in on the terrified sardines. The full power of their fearsome bills was on display as they bisected the baitball and collided with the helpless fish.

I was glad digital photography did not limit me to only 36 shots, as film did. How could I possibly pace myself with all the constant action? Gratefully, I did not have to, so I kept photographing the scene.

Some sea lions joined the hunt and helped the marlins with corralling the sardines close to the surface to make feeding easier. The marlins were more cautious about attacking the baitball when the sea lions were around and searched for space between the sea lions’ attacks, perhaps as a precaution to avoid breaking their fragile bills by dashing them against the sea lions.

As more sea lions arrived and gorged themselves on the sardines, the marlins withdrew to search for another baitball. Fortunately, many other such aggregations were in the open ocean outside Magdalena Bay.

Ecotourism

You might think there would be competition between freedivers who wanted to see a marlin underwater and the fishers who wanted to catch and land a billfish. However, as diving with marlins has grown in popularity among in-water enthusiasts, tourist dollars have benefitted the local San Carlos fishing community. Many skippers there have joined together and created a union. Fishers have turned to ecotourism, through which they can make more money than before, putting less pressure on the billfish populations, and ultimately are becoming more aware of conservation and sustainability.

The area now has an influx of people from all over the world. The action attracts commercial and sportfishing yachts, television and movie productions, and pure nature lovers. You will see a range of cameras from smartphones to large digital single-lens reflex and mirrorless cameras.

The action occurs in shallow water, and most shooters do not need strobes, making for less resistance in the water and greater ease of getting in and out of the panga (a small, open, outboard-powered, fishing boat). During the peak season in November, half a dozen to a dozen vessels might be relatively nearby, but they will not all be at the same baitball.

Cooperative operators

Local operators work together in a loose tourism co-op and communicate via marine radio, inviting others to share their good fortune when they find a promising baitball. With their collaborative mindset, it is almost certain that all visiting tourists will return home with stories and images to share. The local guides work hard to train their guests on how to safely approach the baitball without being intrusive. Marlins will leave when people get too close to the baitball, so the objective is to observe without pressuring the marine life.

Local panga operators follow safety protocols, including staying in radio contact with their home base and each other, always returning to shore before nightfall, and reporting when they leave the action zone. They generally travel back to port together in a loose flotilla at the end of the day, which is a prudent arrangement for small boats with single outboard motors, 40 miles offshore.

Luxury liveaboard

Now, after years of experience and continuous search, I have set up a new liveaboard option for experiencing this adventure in comfort and luxury. Introducing the catamaran Mango Wind. The vessel is 45ft long and 24ft wide. The vessel offers three large cabins, with one queen-size bed, private head and shower, and individually controlled air conditioning. The vessel has a water maker and all the latest navigation and communications equipment.

The crew on board includes a chef, divemaster, skipper and BigAnimals expert expedition and photography leader. We offer the luxury catamaran adventure to only three unaccompanied guests or a mix of a couple and a solo guest.

The stable Mango Wind catamaran is our floating hotel. The vessel will moor in a safe, quiet bay at the entrance to Magdalena Bay and the Pacific Ocean, at least two hours away from the nearby town of San Carlos.

The logistics save two hours daily getting out to the site and two hours returning to the hotel. We are first each morning to the staging area of the sardine and the marlin action, and we stay at sea after everyone else leaves at 3 p.m., so we can enjoy the beautiful warm light just before sunset.

Conditions

Weather plays a crucial role in dive travel to this remote area with limited rescue services. Operators will sometimes suspend their trips, particularly when there are strong winds. Instead of heading out to sea, the skippers will operate within the more protected waters of Magdalena Bay. While it may not be the intended destination, the bay can also offer fascinating encounters. An extensive sand dune zone on the northwestern corner of the bay has elaborate water channels and a healthy mangrove habitat. There is a vibrant population of fish, cormorants, pelicans and other bird species. You may even see a coyote or a bald eagle. This mangrove wonderland might not be the hook that brings you to Magdalena Bay, but the time you spend exploring the mountainous Isla Magdalena and Isla Santa Margarita will inspire you.

Tiger sharks

From November through January, the baitballs attract wildlife other than marlins, including tiger sharks. Tiger sharks change the vibe, so we stay vigilant and take the precaution of turning off bright video lights. The sharks are quite possessive of the baitball, and we are deferential to our place in the food chain.

Orcas

A pod of orcas visits two or three times during a season, generating much excitement. Once, while we were sitting in the panga, a burst of rapid conversation lit up the airwaves. Several pangas left their baitballs to rendezvous with the fisher who spotted the orcas and alerted his buddies. It was extraordinary to swim for two hours with a pod of six transient orcas. One of the females carried a piece of shark meat in her jaw and brought it close to the panga. After taking a few images of her above water, my team and I joined the pod in the water for a peaceful and nonthreatening encounter—an experience that will never leave me.

Humpback whales

In November and December, humpback whales migrate south to the warm waters of Panama and Socorro to socialize and give birth. We were able to swim with a mother and calf several times. That same season, another team had a remarkable experience swimming with blue whales migrating south toward the Sea of Cortez.

Mobula rays

Mobula ray encounters off Magdalena Bay are fantastic as well. When the sea was too rough to cruise to the sardine grounds and the wind had dispersed the frigatebird flocks, our experienced skipper suggested we head out to sea. After an hour or two of watching for whale spouts, someone saw a breaching mobula.

That is one thing about the Mexican sardine run—it pays to be flexible. Whatever you thought you might photograph in the morning may not be the images you end up editing at the end of the day. Despite the change in plans, the massive school of mobulas made us very happy.

Bryde’s whales

Our final notable encounter on this trip was with a Bryde’s whale. Although they are smaller cetaceans, slightly shorter and lighter than humpbacks, Bryde’s whales still take your breath away. The whales may quietly arrive while you are focused on a baitball or darting marlin. With their giant mouths gaping wide, they will surprise you by suddenly swooping in and engulfing almost the whole baitball at once.

Bird Island

If you do not mind getting up a bit early, you can head out to sea at 5:30 a.m. to see the sunrise over Bird Island. You will not regret it. The island can accommodate thousands of cormorants and pelicans.

While looking at some of my drone footage taken from high enough above the island to avoid disrupting the birds below, I noticed that the island was shaped like a heart. Only then did I discover the symbolic heart of Magdalena Bay, pulsing with life both above and below the sea.

For more information or to make a reservation for the Mexican Sardine Run expedition, go to: BigAnimals.com/expedition/striped-marlin.

Visit BigAnimals.com or email: amos@biganimals.com