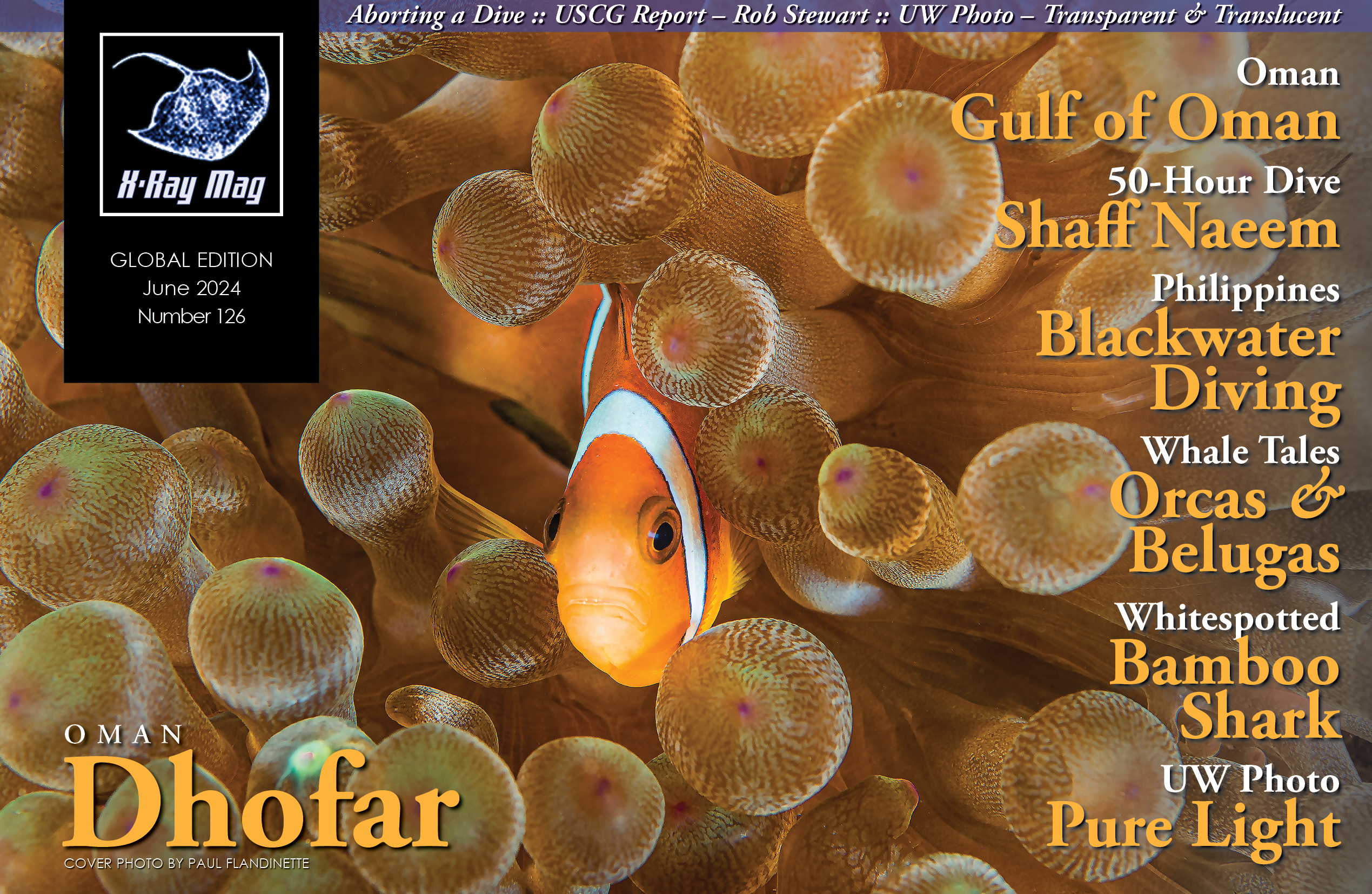

In Oman, there is plenty of diving to enjoy and marine life to observe in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman. Pierre Constant shares his adventure there.

Contributed by

Stretching along the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, between Africa and Asia, Oman is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the southeast, the Gulf of Oman to the northeast, and the Persian Gulf to the northwest. It has a land area of 309,000 sq km and 3,000km of coastline. Its immediate neighbours are Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemen. Iran lies to the north, across the Strait of Hormuz.

Oman lies between 16° and 28° N latitude and 50° and 60° E longitude. It comprises mostly gravel desert plains, with the Al Hajar mountain range along the northeastern coast and the Dhofar mountains along the southeastern coast. Muscat, the capital of Oman, is located at 23°35’20” N and 58°24’30 E. Oman is an absolute monarchy with a population of 5,492,196 and is under the rule of Sultan Haitham bin Tariq—successor to Sultan Qaboos bin Said, who passed away in 2020.

Historical background

Early human populations migrated from Africa to Arabia in the late Pleistocene. Discovered in 2011, a site belonging to the African lithic industry was attributed to the Arabian Nubian complex and dated to 106,000 years ago. The first settlers arrived from Yemen in the 8th century. Over time, tribes from western Arabia settled in Oman for fishing, farming and herding.

The Omanis adopted Islam in the 7th century. The Omani Azd established the Imamate of Oman and built a maritime empire whose fleet controlled the Gulf. Under the influence of the Seljuk Empire in the 11th and 12th centuries, the Omani coast fell to the Nabhani dynasty until 1507.

The Portuguese captured Muscat and occupied it for 143 years, from 1507 to 1650. Colonisation was extended to the north and south to control access to the Persian Gulf. Muscat fell briefly to the Ottoman fleet in 1552.

In the 17th century, the Portuguese fought a major naval battle in the Persian Gulf against an armada from the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the English East India Company. It ended in a draw and a loss of influence for Portugal. The Omani Imams took over, establishing a maritime empire in East Africa and even fighting the Persians in the process.

To block commercial competition from the French and the Dutch, the British signed treaties with the sultans in the late 18th century. British influence grew until the end of the 19th century.

A major slave market and producer of cloves, Zanzibar became a part of the Oman Empire and was chosen as its capital in 1887. Zanzibar and Muscat later became two separate sultanates.

Oil reserves were discovered in Dhofar in 1964. Following the Dhofar rebellion in the 1960s, Sultan Said bin Taimur was deposed by his son, Qaboos bin Said, in 1970. The latter opened up the country with economic reforms and modernisation, spending on health, education and welfare. Slavery was outlawed. Qaboos died in January 2020 and was succeeded by his cousin, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq.

Dive centre

Anticipating my arrival, Lauren Davies, the Welsh manager of Musandam Discovery Diving, greeted me with smiles at Khasab Airport. I was driven to the staff villa, which also served as the company’s guesthouse on the outskirts of town. The dive centre was downtown, conveniently located on a canal not far from Dhow Harbour, where all the tourist cruises departed from. The only dive operation in Khasab, Musandam Discovery Diving was founded in late 2015 by the friendly 37-year-old Bader Al Shehi. Dressed in the dishdasha, a traditional Omani white robe, with kummo (prayer hat) and mussar (red and white turban), Bader also works in the oil and gas industry.

“You’ll be able to dive with Bader on Saturday,” confirmed Lauren. “He is a very busy man but very fond of nudibranchs!” she added with a smile. The dive centre was very professional, with a classroom for instruction and a convivial wooden terrace overlooking the water. The dive boat was a 35ft Sinbad fibreglass speedboat from the UAE with twin 225 Mercury outboards. It had tank racks and comfy benches along the sides and a capacity of ten divers, ideally. Dive instructor Calton and his wife, Tasnee, the divemaster, were both from Kerala in South India. Hamud, the first boat captain, was from Oman and spoke English. Mahesh, the other boat captain, was from Kerala and spoke fluent Arabic, having worked as a fisherman for many years.

Topside attractions

Lauren drove me to the main harbour, then to the gigantic Lulu Hypermarket near the dive centre, and finally to the old Khasab Castle. A Portuguese fort built in the 17th century and refurbished by the Omani sultans, it had interesting historical displays and informative panels on geology and natural history. As we strolled around the bulwarks, we were greeted by mynahs, pigeons and joyful green, black and rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri) nesting in the holes or playing in the native palm trees. It was a must-see attraction with an entrance fee of 3 OMR. However, a sudden heavy downpour forced us to retreat indoors. Some of the streets in Khasab were flooded in no time.

Musandam Peninsula

Isolated far to the north, between the claws of the UAE, the mountainous Musandam Peninsula is a separate enclave of Oman. It is 90km long and 35km wide, with an elevation of 2,100m at Jebel Harim. The Musandam is made up of 270-million-year-old Permian limestone and a 3,300m thick Jurassic and Cretaceous carbonate shelf. Pale grey and reddish, it consists mainly of hard dolomite.

Eighty-five to 15 million years ago, when the continental plate of Arabia collided with the Eurasian Plate, these limestone deposits were uplifted from the seafloor by tremendous tectonic forces and folded into what are now the Musandam mountains. A complex geological phenomenon of subduction/obduction occurred when the Arabian Trias-Jurassic crust went under, then collided with, the western Iranian Makran continental margin, creating the Zagros Mountain range in Iran and the Al Hajar Mountain range in northeastern Oman.

Dive sites

Aquarium. The first dive site was at the base of a Cretaceous cliff at the entrance of Khawr Ghubb Ali fjord. Underwater visibility was poor, with lots of particles in the water. The rocky bottom was uninspiring. However, there was fish life, mainly yellowbar angelfish (Pomacanthus maculosus), schools of long-spot snappers (Lutjanus fulviflamma), parrotfish species and what looked like a peacock grouper, which was brownish red with blue dots and had a yellowish saddle on the caudal peduncle. A regional endemic, a yellowfin hind (Cephalopholis hemistiktos) I spotted here, was rather shy. A cowtail stingray (Pastinachus sephen) gazed stoically at me from the sandy seabed. The water temperature was a balmy 30°C.

Humsi wreck. At the entrance of Khawr Shamm was the next dive, the Humsi wreck. A 10 to 11m-long fishermen’s landing barge, it was all rusted and deliberately sunk in 10m (~33ft) of water some years ago. Closer to Khasab, the visibility was that of a pea soup. “The sea has been rough lately. It’s been raining too,” explained Calton.

I noticed schools of Arabian monocle bream (Scolopsis ghanam) and variable-lined fusiliers (Caesio varilineata). A small group of pearly goatfish (Parupeneus margaritatus) hovered over the deck. Two shrimp gobies were on the lookout at the entrance of a burrow in the sand. A short distance from the wreck, some pyramid-shaped metal structures had been installed to aid the replanting of staghorn coral.

With strong winds the next day, the dive was cancelled. The suggestion was for me to go on a dhow cruise—on a traditional wooden boat—in the Shamm fjord. It was very scenic and gave great views of the Trias-Jurassic-Cretaceous cliffs of the Musandam Peninsula as the boat passed by fishing villages. It was also an incredible opportunity to see the normally elusive Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea), which followed the boat, porpoising in a playful display.

Currents and marine species

Located in the eastern horn of Arabia, Musandam lies between the Persian Gulf to the west and the Gulf of Oman to the east. The role of marine currents in the region is complex and not well understood.

Two main bodies of water appear to be at work, including the Persian Gulf Water (PGW), which flows northwest to southeast into the Strait of Hormuz, and the Indian Ocean Surface Water (IOSW), which flows southwest to northeast along the coast of Oman in the Arabian Sea from Salalah to Ras Hadd (on the eastern cape of Oman) with a diversion into the Gulf of Oman along the coast of Iran. A prominent “upwelling” zone can be seen at Abu Rashid Island on the eastern side of Musandam, with cold water coming up from the deep.

In his book Coastal Fishes of Oman (published in 1995), the renowned American ichthyologist John E. Randall reported a total of 1,078 species in the country and its islands. The most recent list of reef fishes (updated in 2010) recorded 1,179 species (including freshwater species) belonging to 527 genera and 165 families. Of these, 29 marine fish species are endemic to Oman (2016).

The northern part of the Musandam Peninsula is accessed via Khawr Al Quway, a fjord that separates the military island of Umm Al Ghanam from the mainland. The water is clearer here, and underwater visibility is even better when the sea conditions improve with stable weather.

Abu Sir and Al Khayl Islands

Coral Garden. This dive site at Abu Sir Island was at the base of a Cretaceous limestone cliff. At a depth of 20m, the surprise was finding blueish-purple gorgonians and yellow bushes of black coral (Antipathes sp.). The water was clear but still greenish. I noted the presence of yellowbar angelfish, yellowfin hind, variable-line fusiliers, gold-spotted jacks (Carangoides bajad) and the regional endemic Arabian butterflyfish (Chaetodon melapterus), which was yellow with a black bar on the face. The black-spotted butterflyfish (Chaetodon nigropunctatus) was rather common, and schools of threespot dascyllus (Dascyllus trifasciatus) and silvery grey sordid sweetlips (Plectorhinchus sordidus) roamed at depth.

Cat’s Eye. A 30-minute boat ride to Al Khayl Island brought us to a striking cat’s eye rock formation carved into the Jurassic limestone. Many hard corals were found here, including Porites, Acropora, Montipora and Pavona sp. There was good fish life. I saw pretty cushion stars (Culcita coriacea) on the sand as well as the blue-black predatory crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), which has caused a lot of damage in Musandam.

A slight eastward current was felt here. At 15m a rather charming nudibranch, Hypselodoris pulchella, caught my eye. It was white with yellow spots and a purple-edged girdle. Its gills and rhinophores were also purple. This dorid of the Chromodorididae family is found from the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean.

Al Batinah wreck. On the other side of Al Khayl Island, behind Cat’s Eye, was a secluded cove. An Oman Navy patrol boat had just been sunk here on 7 February 2023 after 30 years of service. About 15m long, it lay upright on the sandy sea bottom at 22m. It already had a lot of concretions. Red and orange encrusting sponges covered the edges of the deck colourfully against an eerie apple-green background. Penetration was possible in the hold and in some of the corridors inside. Yellowbar angelfish were present, as were two round batfish (Platax orbicularis), twobar seabream (Acanthopagrus bifasciatus), some pennant coralfish (Heniochus diphreutes) and cushion stars.

On weekends, expats often drive down from Dubai two hours away. Bader, the dive centre owner, showed up on Saturday.

No Palm Beach. East of Musandam Island is a little beach in a secluded bay surrounded by mountains. At Smirnoff Point, an illegal shipment of vodka bottles had been dumped by smugglers trying to evade the coastguard. It was found by divers.

The water looked clear from the surface but was murky again at depth. Underwater, there were huge boulders and bushes of black coral hosting giant oysters in clusters. Bader pointed out a yellowmouth moray (Gymnothorax nudivomer), which was brown with white dots. Some round batfish hid under a ledge. Rusty parrotfish (Scarus ferrugineus) roamed around, and the Sohal surgeonfish (Acanthurus sohal) foraged in the shallows. Twobar seabreams were common.

Abu Rashid Island

Musandam Discovery Diving visits up to 24 dive sites around the peninsula. The very best of these are at Abu Rashid, the northernmost island. When the Gulf of Persia is as smooth as an oil slick, and the sea conditions are perfect, it is the right time to go.

Abu Rashid drift dive. On the west side of the island, there was a succession of slopes and ledges in various steps. Bushes of black coral decorated the depths. In the shallows was an enchanting prairie of yellow and white soft corals (Dendronephthya klunzingeri) with patches of red sponges in between.

The fish seemed tame here as the visibility improved. Large sweetlips and snappers were spotted along with clouds of the redtoothed (blue) triggerfish (Odonus niger) with white tails. Big painted lobsters hid under ledges, and the Arabian picassofish (Rhinecanthus assasi) wandered around.

On the east side of the island, the wall at Abu Rashid has a prominent drop-off and a thermocline at 15m. An upwelling of cold water from the deep created a sudden blurred layer. The water temperature suddenly dropped to 26°C. For the fourth time in the last four days, I could not do the second dive—because I could not clear my left ear. I suspected that bacteria from algae had caused an infection. There was no option but to administer ear drops, with mixed results.

Topside excursions

When not diving, a worthwhile excursion is to drive west along the coast to Qiba and inland to the village of Tawi. Here, 3,500-year-old rock engravings of a hunter on a horse and camels can be seen on different boulders on the left side of the road. Further along the coastal road to Dubai, the old fort of Al Bukha is perched on a hilltop with a good viewpoint overlooking the surrounding area. On the way back to Khasab, a dirt road up to Al Harf leads to the top of the mountain. A breathtaking panorama of Musandam’s geological wonders awaits to the east, with views of the village of Mukhi blending into the environment. Looking to the west, the top of the cliff overlooks the picturesque coastline of the Persian Gulf and the town of Al Bukha.

Back to Muscat

An Oman Air flight took me back to Muscat. Then, a one-hour taxi ride across a rugged, mountainous landscape of red and black rock formations brought me to Jebel Al Sifah. An artificial paradise in the middle of nowhere, it was a retreat for idle holidaymakers with a taste for luxury, a swimming pool and a marina. Not my kind of heaven, though.

The Extra Divers dive centre was a ten-minute walk in the sun along the glistening waters of the marina. Swiss manager Guillaume Chapuis greeted me on the way. With blond hair combed back and a salt-and-pepper beard on a square chin, he reminded me of Kit Carson or David Crocket. “I’m on my way to lunch,” he said. The connection in our ensuing chat was immediate. Guillaume was a former banker involved in the high spheres of finance before changing his life to run a dive centre in Malta.

The diving at Al Sifah in the Gulf of Oman covered three different areas: Abu Daud Island to the southeast, Bandar Al Khairan to the west and Fahal Island, which was much farther away into the blue, depending on sea and weather conditions. Altogether, the dive centre ran trips to 30 dive sites.

Abu Daud. There were two main dive sites here. One was West Corner, and the other was East Corner. Elongated and shaped like a tibia, the island attracted great blue herons. Schools of golden or ring-tailed cardinalfish (Apogon aureus) hovered in small caves. Charged with plankton, the green waters were subject to a slight current from the southeast.

I came across the Gardiner’s butterflyfish (Chaetodon gardineri), the laced or honeycomb moray, the Sohal surgeonfish, the redtail butterflyfish (Chaetodon collare), the yellowtail tang (Zebrasoma xanthurum), which was royal blue with a yellow tail, and the blackspotted rubberlip or sweetlips (Plectorhinchus gaterinus). The pretty Arabian picassofish was always wary of photographers. A little school of speedy diamondfish (Monodactylus argenteus) zoomed back and forth under the surface.

First Entrance. Located in Bandar Al Khairan, this dive site was a mixture of boulders and a white sandy bottom. Anna Sara, the Finnish dive instructor, pointed out a marbled torpedo ray (Torpedo sinuspersici) that commanded respect. Numerous yellow-spotted burrfish (Cyclichthys spilostylus) rested on the slope. A forest of black coral concealed a large hawksbill sea turtle munching on yellow polyps. A school of bigeye snappers (Lutjanus lutjanus) hovered about, together with the Arabian monocle bream. A few flower sea urchins (Toxopneustes pileolus), with pieces of shell attached, dotted the sand.

Mermaid Cove. This dive site had roughly the same seascape as above. In between purple gorgonians, a green sea turtle dozed on a rock. A tandem pair of Hypselodoris pulchella nudibranchs cruised on the face of a large boulder. Above a sandy patch, two cuttlefish were engaged in a courtship display. Blacktip jacks (Caranx heberi) flashed by me towards the end of the dive along the rock face. A vast field of Sarcophyton sp. soft corals carpeted the shallows.

Al Munassir wreck. Once a British-made amphibious warfare vessel, this 84m-long ship was launched from Glasgow in 1978. Sold to the Oman Navy as a helicopter and small vehicle carrier, it was in service for 25 years with a crew of 45 and nine officers. It sank on 22 April 2003 near Al Khairan, and is now lying upright in 25m of water.

The visibility was great, and so was the marine life. Richard, the Irish dive guide, took me from the bow to the stern. The winch area was full of colourful Dendronephthya sp. soft corals teeming with fish, including golden cardinalfish, redtail butterflyfish and yellowbar angelfish. Dark and silty, the nearby deep hold was a garage for helicopters.

We cruised along the gangway on the port side, which was exposed to the sun’s rays. Various penetrations inside offered an eerie feeling, with beams of light gushing through the portholes. Schools of long-spot snappers and bigeye snappers fluttered around the gun emplacements and superstructure. Male and female bluetail trunkfish (Ostracion cyanurus) were easily approached and showed no fear.

Final thoughts

Before I ascended to the safety stop, a honeycomb moray slipped out of hiding to meet me, joined soon after by an equally inquisitive grey moray (Siderea grisea). This last image encapsulated perfectly both the thrill and the enchantment of diving in Oman’s waters. “I know it is not the last time we see each other,” concluded Guillaume on the morning of my departure. Oman’s great south beckons…

Sources:

Al-Abdessalam TZS. 1995. Marine Species of the Sultanate of Oman. Muscat (Oman): Marine Science and Fisheries Centre, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Clarke MH. 2006. Oman’s Geological Heritage. Petroleum Development Oman.

Fishbase.se

Flandinette P, Claereboudt M. 2021. Secret Seas. French. Omran Group.

Pous S. 2005. Dynamique Océanique dans les Golfes Persiques et d’Oman. Université de Brest.

Wikipedia